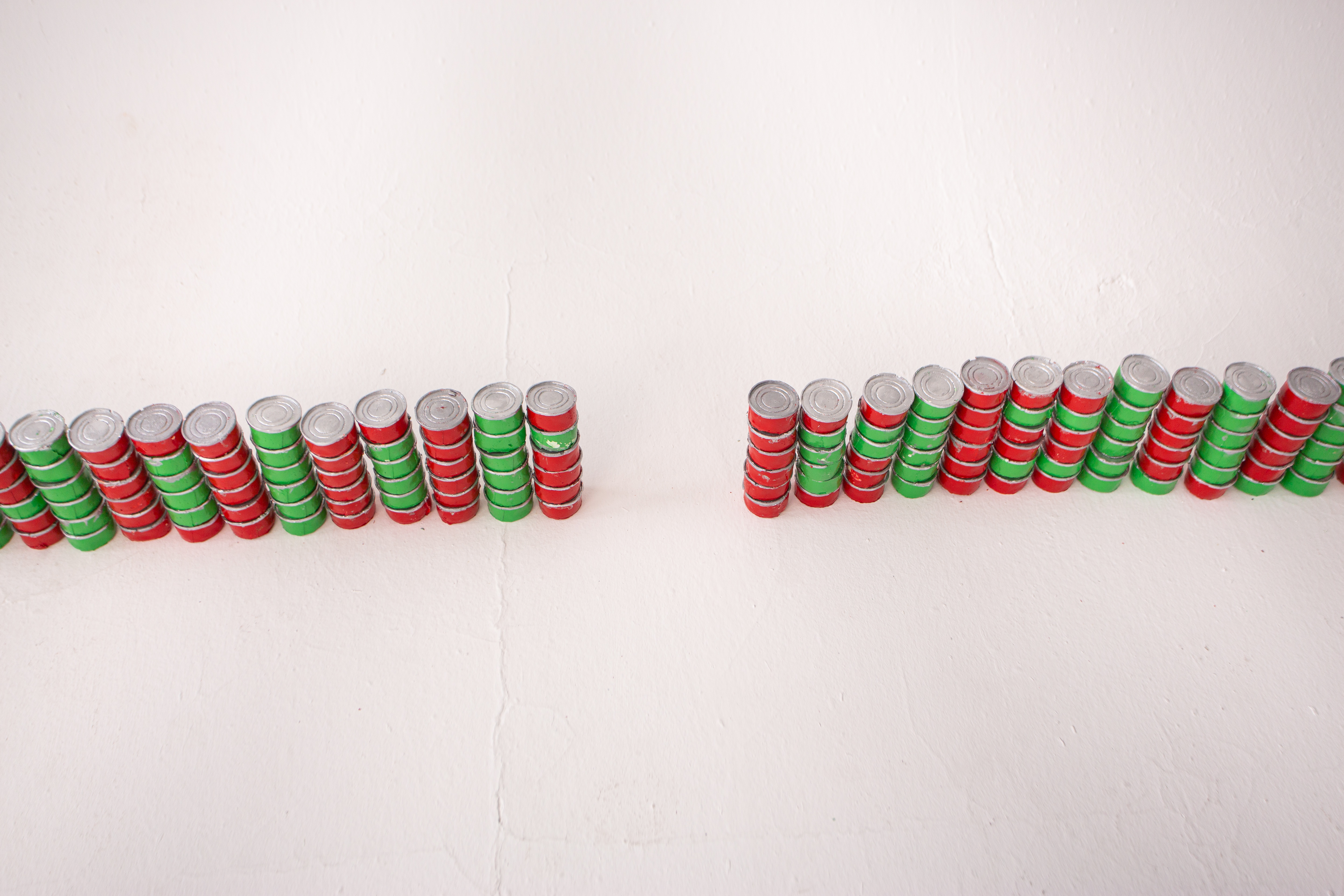

Rooi Gevaar, 2022

plaster of paris, enamel, spray paint

“the SADF troops pertaining to Operation Savannah had many tactics to avoid leaving a trace. one of them was stripping all cans in ration packs of labels and, in place, painting and colour coding them”